"I want to be a useless tree"

On Zhuangzi, siren songs, capitalist productivity and social media hypervisibility.

Sex doesn’t always sell.

My time as a relationships, reproductive health, kink and dating reporter was not rewarded with a living wage. An insidious truth about Doing the Work is that it often seldom pays the bills. Many of you may be surprised to learn that a so-called progressive, liberal movement isn’t the inclusive, equitable, free-wheeling and generous utopia conservatives fear.

If you’re trans, Black, fat and not able-bodied, it’s hard to become anything but a token.

As was common for “content creators” on my beat, from 2019 on, I took on gifted and paid partnerships with sex toy companies in my field, freelanced and made video content — anything I could use to live above the poverty line in a suburb of Washington, D.C. Anything I could use to build my brand to catapult myself above that line. Permanently.

I cannot overstate this: Being a professionally sexy content creator was sexy until it wasn’t.

It was a bit of an ego crack to take time off from paid partnerships. I got a full-time job with benefits, a living wage, and editors who didn’t make me feel like I was stupid. Sorry if I didn’t want to chase brands down for checks anymore!

And I suffered for it. My engagement dipped dramatically. The post-George Floyd white guilt money for smaller Black creators dried up. PR people kept sending emails but stopped returning them, once they realized their mistake: There was no real clout I could offer them.

I slipped into a debilitating depression, as my increasingly toxic relationship, fraught family relationships, lack of a solid friend group to pick up that emotional slack, money problems, plus-size status, debilitating chronic pain, sense of imposter syndrome and overall negative self-image squeezed me down like one of those for-kids puréed fruit pouches.

We all know our social media addiction is, quote fingers, “bad,” but just like vaping, binge-drinking, numbing our pain with serial monogamy or work, and eating our feelings, we do it anyway because we literally can’t stop. And if we could stop, we don’t want to imagine our lives with that new reality — it’s inconceivable to us.

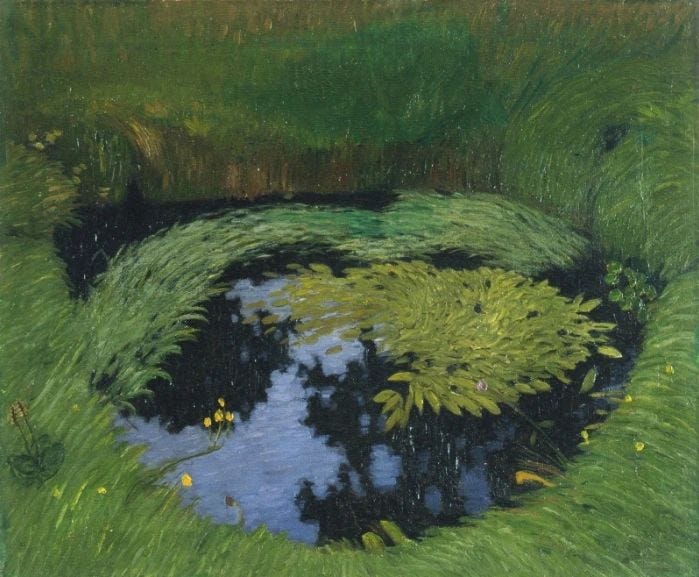

I’m struck by the tale of “The Useless Tree,”1 which is a teaching of Taoist philosopher Zhuangzi (or Zhuang Zhou, or Chuang Tzu).

Carpenter Shih went to Ch’i and, when he got to Crooked Shaft, he saw a serrate oak standing by the village shrine. It was broad enough to shelter several thousand oxen and measured a hundred spans around, towering above the hills. The lowest branches were eighty feet from the ground, and a dozen or so of them could have been made into boats. There were so many sightseers that the place looked like a fair, but the carpenter didn’t even glance around and went on his way without stopping.

His apprentice stood staring for a long time and then ran after Carpenter Shih and said, “Since I first took up my ax and followed you, Master, I have never seen timber as beautiful as this. But you don’t even bother to look, and go right on without stopping. Why is that?”

“Forget it—say no more!” said the carpenter. “It’s a worthless tree! Make boats out of it and they’d sink; make coffins and they’d rot in no time; make vessels and they’d break at once. Use it for doors and it would sweat sap like pine; use it for posts and the worms would eat them up. It’s not a timber tree—there’s nothing it can be used for. That’s how it got to be that old!”

After Carpenter Shih had returned home, the oak tree appeared to him in a dream and said, “What are you comparing me with? Are you comparing me with those useful trees? The cherry apple, the pear, the orange, the citron, the rest of those fructiferous trees and shrubs—as soon as their fruit is ripe, they are torn apart and subjected to abuse. Their big limbs are broken off, their little limbs are yanked around. Their utility makes life miserable for them, and so they don’t get to finish out the years Heaven gave them, but are cut off in mid-journey. They bring it on themselves—the pulling and tearing of the common mob. And it’s the same way with all other things.”

I’ll stop here and assert: We think about ourselves and each other the way that Carpenter Shih thinks about the worthless tree.

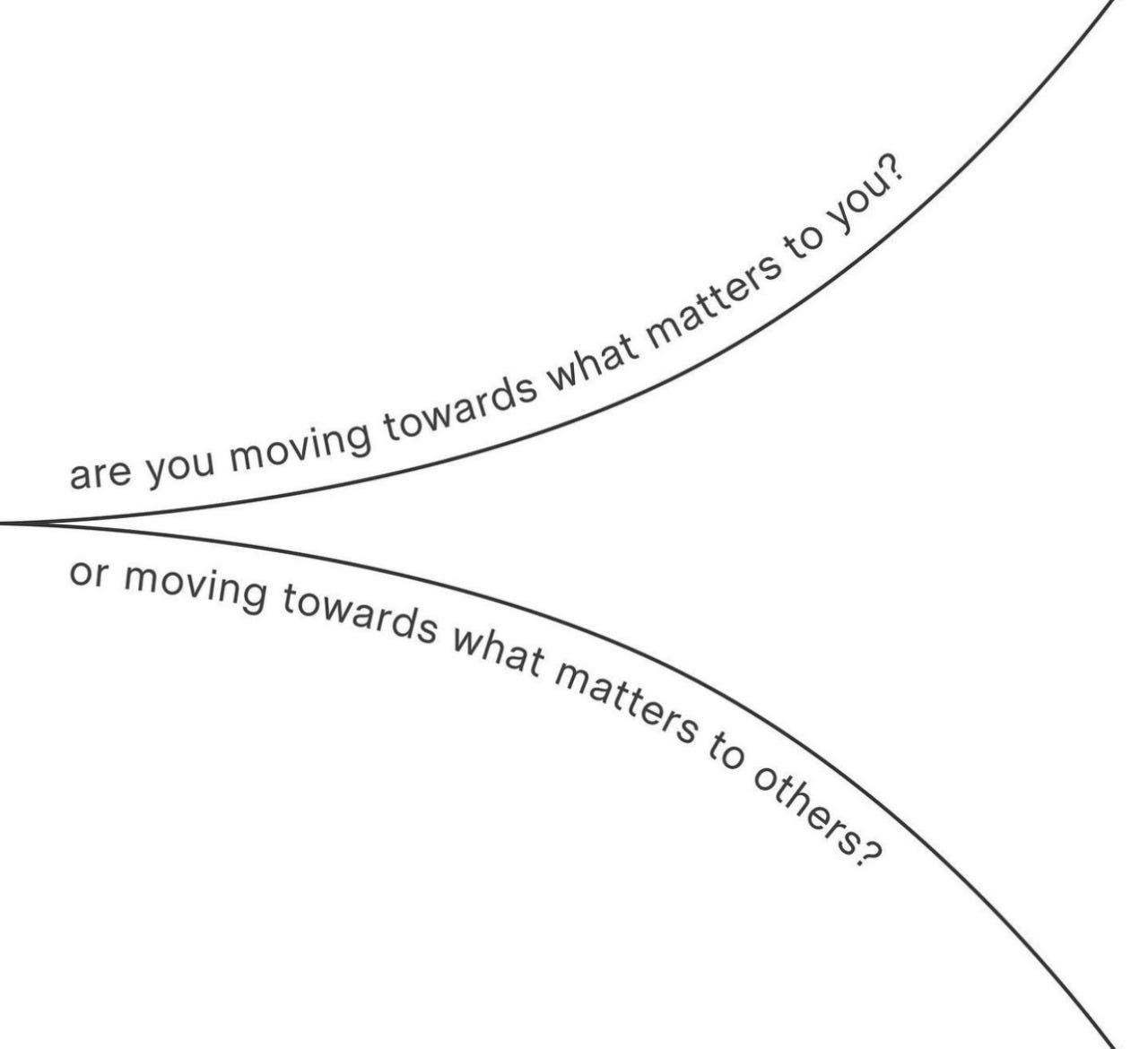

I know I have been guilty of almost subconscious scorekeeping:

Isn’t there something I need to be doing right now?

Isn’t there something I could be doing right now?

Have I seized the day2 and been as productive as possible?

As a salaried worker: Have I done $XX,000 worth of work this week? (Especially as entry-, junior- and senior-level white-collar workers are all sent to the slaughter.)

As a remote worker: In spite of being physically separated from my coworkers, have I made my daily impression as a person of value to my team? To my boss? To the company?

Reading Zhuangzi’s fable, I’m affirmed in my belief that I don’t want to be useful 100% of the time. As scary as it feels to type this, I think I’m actively trying to be “useless”3 this year.

After detailing the abuses the trees face for bearing fruit, the oak tree continued:

“As for me, I’ve been trying a long time to be of no use, and though I almost died, I’ve finally got it. This is of great use to me. If I had been of some use, would I ever have grown this large? Moreover, you and I are both of us things. What’s the point of this—things condemning things? You, a worthless man about to die—how do you know I’m a worthless tree?”

And it’s this part of the story that is extremely poignant to me. Through the oak tree, a man who was born in 369 B.C. touches on the sociocultural, economic, and environmental issues plaguing us today: extraction and overconsumption, pursuit of profit margins through eco-capitalism, the neo-colonial reality in which human needs and values trump that of the Earth.

Where does this leave me with Instagram?

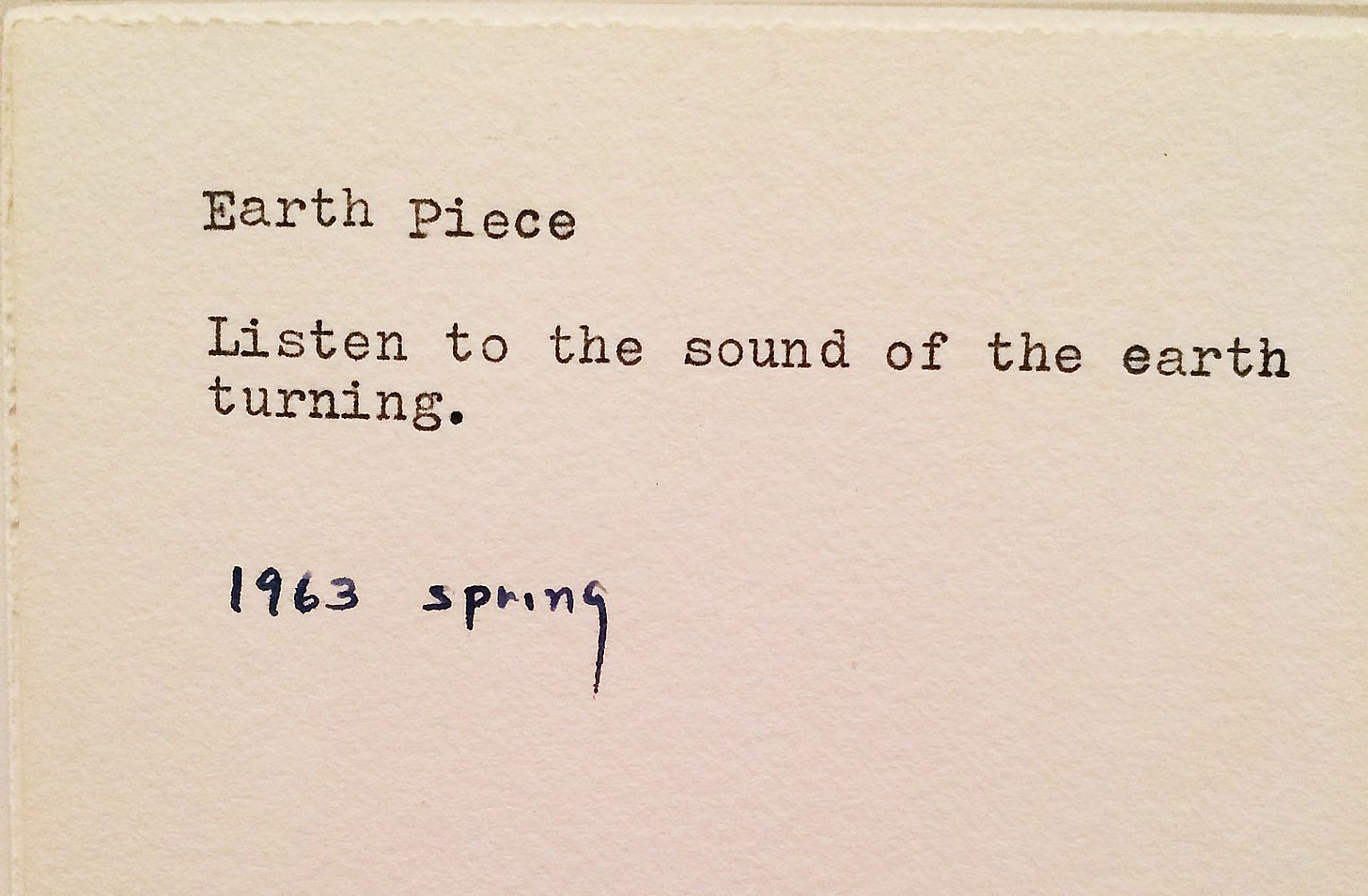

I first came across Zhuangzi’s fable in Jenny Odell in the introduction of her book about resisting the “attention economy.” Finishing that book in fall 2023 spurred me to action — or rather, inaction. I started plotting ways not to leave Instagram but to change the way I engage with it.

I started posting more mood boards and less “my life in squares." I don’t see the value in sharing bits of my personal life on the grid anymore — and I’m not dunking on those that do.

I’m reminded of Odell’s observations about social media breaks in her aforementioned book: “Facebook abstention, like telling someone you grew up in a house with no TV, can all too easily appear to be taste- or class-related.”

Unpacking this study on “conspicuous non-consumption” and the “performative” nature of Facebook abstention, Odell quotes the media researcher, saying that refusal to be on social media can be seen as “holier-than-thou internet asceticism” and a decision to be actively anti-social.4

I personally just think my life is too precious for the ex-friends, ex-flings and ex-undergrad lurkers from my alma mater, who cast the evil eye, who surveil, who gaze and don’t engage, who make me feel like I’m in a panopticon of intimacies and not a funny sexy cool internet space when I post on Instagram.

I also feel like I’d be making it hot if I just blocked all of these people. (Also, Meta has punished me before for this half-step digital detox and has restricted my account several times for engaging in “suspicious” activity.

That totally makes sense, because renegotiating my relationship to social media and trending toward “digital minimalism” isn’t helpful for a technocratic5 society. )

I remain logged into Instagram on the browser and try to keep the app off of my phone.6 If you see me posting a whole bunch on my IG stories, I’ve fallen off the wagon — I find that my overall screentime goes down significantly when the app is off of my phone, because it’s much more cumbersome to scroll on the browser.

And if you can’t post Stories and clicking through those of your peers is unwieldy, you, as a member of the “Microwave Generation,” lose your nerve to engage in this instant gratification culture.

I’m slowly losing the desire to post on Instagram and it feels good. The discomfort of FOMO is starting to feel like looking in the mirror and catching a glimpse of my quads or a whisper of 4-pack forming. I can say, “This pain is worth something.”

I’m grateful for the deepening of my attention — moving away from doom-scrolling and foraging fodder for self-loathing.

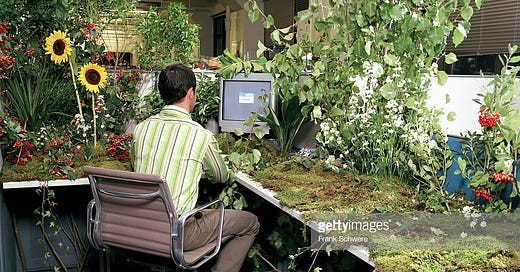

I’m enjoying starting a career7 in environmentalism, conservational admiration, climate justice advocacy, and ecological exploration, with Swimming Home as the touchpoint. As I replace my Instagram time with letter-writing, I’m excited to figure out more avenues that enable myself and others to be as useless and beautiful as an astral-projecting tree.

And I’m finally starting to be okay with the unsexiness of that.

Liked this post? Share “Swimming Home” with a friend and make sure you’re subscribed — so all this yummy decolonial / ecological thought gets straight to your box!

⋆⭒𓆟⋆。˚𖦹𓆜✩⋆

Thank you Sara for copy-editing today’s essay!

From “Chuang Tzu: Basic Writings” as translated by Burton Watson (1996), pp. 59-61.

I’m interested in seizing the day, but with pleasure — not productivity.

Useless to capitalism, but useful to the collective, to plants, to dogs, to bugs, to the air and to the rivers.

As Odell illustrates in her book, “refusal in place” of social media and other forms of the attention economy is a privilege. And while my point in putting together this Substack post wasn’t to argue this point, I hope rewriting this post to include my uncomfortable experiences as a sex educator helps illustrate and acknowledge this point.

tech·no·crat·ic /ˌteknəˈkradik/ adjective — “relating to or characterized by the government or control of society or industry by an elite of technical experts,” per Oxford Languages.

The biggest draw to Instagram Stories is posting thirst traps and cryptic song choices for the Target, as we Gen Zers say. And now I will repeat a bit of Millennial tough love I’ve seen circulating online: That man does not want you and he is not clicking play on that Spotify link.

By Merriam-Webster’s definition, a career can be “a field for or pursuit of consecutive progressive achievement especially in public, professional, or business life.” I don’t necessarily think I’m pursuing this work for profit or to make this my “main hustle.” I’m pursuing this work for my soul and for the bodily salvation of others.